Features

The Principles to Remember When Using 3D Marks and Word Marks Together

Published: October 16, 2024

Marc Groebl Jones Day Munich, Germany

Thomas Traeger Grunecker Patent Attorneys & Attorneys at Law Munich, Germany Non-Traditional Marks Committee

Companies want to mention their name or brand on a 3D mark to raise the consumer awareness about the origin of the product. But will the 3D product still be seen as a separate identifier if it is branded with a word mark? Does publicizing the shape influence consumer perception? Marks like the 3D RUBIK’S CUBE draw attention because they are well known. Other less-known shapes require a significantly different appearance from their rival products to meet the threshold of being acknowledged as a 3D trademark.

This article outlines the leading principles set by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and analyzes how the German courts, the General Court of the EU, and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) implement the CJEU principles to deal with the business practice of using 3D marks and word marks together. To maintain its enforceability, the 3D mark must have been put to genuine use within a period of five years following registration. This postulates a specific use of the registered mark that is capable of fulfilling the essential function of a trademark to guarantee the identity of the origin of the marked goods or services to the consumer. The CJEU’s principal requirement to accept joint use as genuine is that the 3D mark must continue to be perceived as indicative of the origin of the product at issue (CJEU, 18/4/2013, C-12/12 – Colloseum/Levi, para. 35).

On one hand, the law partly recognizes an economic need of the companies. The law allows the proprietor of the mark to make variations of the sign. It confers discretion to better adapt the mark to marketing and promotional campaigns (CJEU, July 18, 2013, C-252/12 P – Specsavers, para. 29).

On the other hand, the law considers trademarks as source identifiers. Trademarks must allow the consumer to differentiate the origin of a product from that of another product. If a trademark is changed too much, it may make the consumer believe that a different owner is responsible for the new trademark. Framed within this legal background, to guarantee the identity of the commercial origin of the goods or services, use may not alter the distinctive character of the mark in the form in which it was registered.

The CJEU’s principal requirement to accept joint use as genuine is that the 3D mark must continue to be perceived as indicative of the origin of the product at issue.

The Bullerjan Case

The Bullerjan case did not deal with a well-known 3D mark, only with the shape of a peculiar-looking oven shown below. The proprietor defended a revocation action against its 3D mark of the oven that was used together with the word mark BULLERJAN. In its decision, the CJEU laid out general principles that help the courts and intellectual property offices assess the genuine use of 3D marks if and when they are used together with word marks. In such cases, it is necessary to decide whether the addition of the word mark renders the 3D mark different from its registered form. The Bullerjan judgment shows that the CJEU has applied a two-step test (CJEU, Jan. 23, 2019, C-698/17 P – Bullerjan II, paras. 33, 30, 32, 34, 44, and 41) that was also applied in the earlier Lotte case (CJEU, Sept. 7, 2016, C-586/15 P – Lotte, para. 30).

First Step—Assessing the Degree of Distinctiveness of the 3D Mark

For the test’s first step, the CJEU raised the following questions regarding the degree of the distinctiveness of the 3D mark in assessing the degree of functionality of the shape protected by the 3D mark in light of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR:

- Does the 3D mark depart significantly from the customs within the relevant sector?

- Does the 3D mark itself constitute an unusual form?

- Does the 3D mark enjoy a high degree of distinctiveness?

Second Step—Assessing Whether the Additional Word Element Causes an Alteration of the Distinctive Character of the 3D Mark

For the second step, the CJEU assessed whether the addition of the word mark to the 3D mark changed the distinctive character, assuming that the word mark’s facilitation to identify the commercial origin of the goods protected by the 3D mark is not sufficient by itself to change the distinctiveness of the 3D mark:

- Does the consumer perceive the shape of the 3D mark as the same, despite the additional word mark?

- Does the word mark cover only a small space of the product’s structure and is it only visible in certain perspectives of the 3D shape?

- To what extent can the word mark be distinguished from the rest of the 3D mark’s structure?

Case Law in Germany

The German courts support genuine use of a 3D mark together with a word mark. Basically, one can infer from German case law that the addition of a distinctive word mark to a 3D mark has been considered less harmful to the genuine use if the 3D mark is a well-known mark. In the case of a 3D mark with a normal distinctiveness, however, the courts have discussed the change of distinctive character more deeply and sometimes refused genuine use.

Appeal Court of Hamburg—LEGO Figure and MONTBLANC Pen

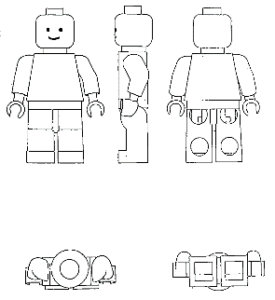

The Appeal Court of Hamburg considered this LEGO figure a well-known 3D trademark:

It then took the view that the neutrally registered 3D mark of a LEGO figure can also be genuinely used with changes, in particular, with added body paintings or inscriptions. The LEGO figure would still be used in a way that preserves the rights in the 3D mark (Appeal Court of Hamburg, Judgment of Nov. 23, 2017, Case 5 U 54/14). In another decision, the Appeal Court of Hamburg did not acknowledge genuine use of the less known 3D shape of a pen cap with three rings:

![]()

In this particular case, the proportions of the 3D mark had been changed and it was used together with the well-known word mark MONTBLANC MEISTERSTÜCK. The degree of distinctiveness of the 3D mark was considered rather limited as many rival products adopted a similar shape. The Appeal Court therefore decided that the use of the well-known word mark MONTBLANC MEISTERSTÜCK together with other changes of the proportions of the 3D mark changed the distinctive character of the 3D mark that did not contain the words “Montblanc Meisterstück” (Appeal Court of Hamburg, Judgment of Mar. 27, 2014, Case 3 U 33/12).

Appeal Court of Düsseldorf The Appeal Court of Düsseldorf did not acknowledge genuine use of a 3D mark in the form shown below on the right:

|

The Appeal Court referred to the Bullerjan case law of the CJEU. The Court presumed in favor of the trademark holder that the addition of the word mark GRASOVSKA alone would not change the distinctive character of the 3D mark (Appeal Court of Düsseldorf, Judgment of Aug. 16, 2018, Case 20 U 59/17). The Court considered, however, that the 3D mark featured only the usual shape of a bottle and that the used form contained too many modifications of this bottle which include the bottle cap, the bottle neck, the bottle body and the relief of a bison on the bottle. These modifications would change the distinctive character of the mark, although the blade of grass in the bottle remains a common characteristic. The Court considered that the blade of grass did not constitute a distinctive feature of the mark as the consumer is accustomed to pickled fruits in all kinds of spirits. The inclusion of a bison grass blade would therefore be understood as a description of the flavor of the spirits only.

EUIPO and General Court

The European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO)and the General Court principally acknowledge the joint use of 3D marks together with word marks. Some of the cases illustrate impressively that special circumstances could bar the joint genuine use of a 3D mark and word mark.

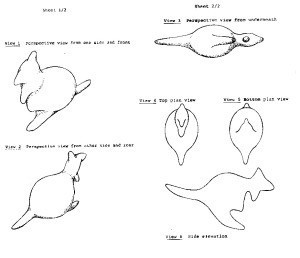

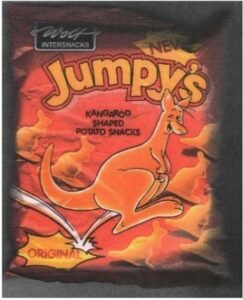

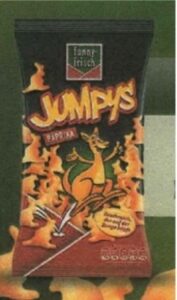

General Court, T-219/17

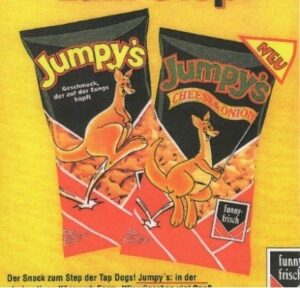

The General Court took the view that the 3D mark for kangaroo-shaped potato snacks (shown above) was not used as a trademark on the following packaging:

|

|

|

|

|

Although the potato snacks in the packaging had the shape of a kangaroo as registered, they were not visible through the packaging. The packaging samples featured 2D pictures of the kangaroo snack almost invariably as a background, incidental, and marginal figure, which is eclipsed by the dominating wordmarks JUMPY’S, FUNNY FRISCH, or WOLF, and the differently stylized figures of a kangaroo in the foreground of the packaging.

The CJEU laid out general principles that help the courts and intellectual property offices to assess the genuine use of 3D marks when they are used together with word marks.

The consumer would therefore perceive the snacks as originating from the company that is identified by the word and figurative marks on the packaging, which, due to their size, color, and proportions, would attract the consumer’s attention more than the 2D representation of the 3D mark. The General Court agreed with the Board of Appeal that the evidence provided could not establish genuine use of the 3D mark.

The degree of distinctiveness of the 3D kangaroo shape could not help. Although 60 percent of consumers knew the shape, only half of them considered the shape as originating from only one source, which was due to the marketing under the different word marks JUMPY’S, FUNNY FRISCH, and WOLF (General Court, Judgment of Sept. 27, 2018, Case T-219/17 – Jumpy’s, paras. 44 and 45).

General Court, T-796/16

The registered 3D mark shown above consists of a commonly shaped bottle with a line on the body which runs diagonally from the left side of the bottle, starting below the neck, to the bottom edge of the base. The General Court referred to the Bullerjan case law and recapped that the weaker the distinctive character, the easier it will be to alter it by adding a component that is itself distinctive, and the more the mark in question will lose its ability to be perceived as indicative of the origin of the product (General Court, Judgment of Sept. 23, 2020, Case T-796/16 – Bottle with diagonal line, para. 140).

The decisions prove that using 3D marks could involve many doubts and pitfalls that companies should be aware of when planning their product marketing.

Proceeding from these principles, the General Court concluded that the inherent distinctiveness of the registered bottle with the diagonal line was weak. The evidence of use that was presented consisted of a bottle that contained a blade of grass rather than a line on the body. Furthermore, a label affected the visibility of the blade of grass. The label makes it difficult to detect what is behind it. The General Court agreed with the Board of Appeal that this changed the weak distinctive character of the registered 3D mark.

EUIPO, R 1546/2008-2

The Second Board of Appeal of EUIPO held that the addition of the word mark RUBIK’S CUBE to the 3D mark did not change the distinctive character of the 3D mark. It is common practice for several trademarks to be attached to a product (BoA of the EUIPO, Decision of Sept. 1, 2009, Case R 1546/2008-2 – Rubik’s Cube, para. 18). The word mark RUBIK’S CUBE is immaterial and does not undermine the use of the 3D mark. The monochrome 3D registration includes all color combinations. Multi-colors do not give the monochrome registration a different distinctive character.

Conclusions

The case law follows the two-step test that the CJEU applied. All decisions consider it possible to use a 3D mark with a word mark. There is no decision refusing genuine use per se just because of the addition of a word mark.

There is some interdependence between the distinctiveness of the 3D shape, the significance of modifications, and the addition of a word mark. The case of the bottle with the diagonal line prominently features the correlation of the weak distinctiveness of the 3D mark and the harm of adding the label. If the distinctiveness is weak in the first step, modifications could make it more difficult to perceive the unusual form in the second step.

The Jumpy’s Kangaroo case was decided between the Lotte decision and the Bullerjan decision of the CJEU. It illustrates that even well-known marks are not beyond adverse changes. Although a lot of consumers knew the kangaroo shape, it could not serve as a source-identifier of a specific company due to the sale under several different word marks. If this had not been the case and the kangaroo 3D mark was well known, the General Court may have had a more difficult assessment and could have decided differently.

In the case of the well-known Rubik’s Cube, the perception of the 3D mark as the same despite the additional word mark was a forgone conclusion.

The decisions prove that using 3D marks could involve many doubts and pitfalls that companies should be aware of when planning their product marketing. Seeking advice from a trademark professional is a mandatory step before a business owner puts their product on the market.

Although every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of this article, readers are urged to check independently on matters of specific concern or interest.

© 2024 International Trademark Association